‘This is art for 2022 – a year of excess after the coronavirus’: CONCRETE speaks to Bora Akinciturk, the multidisciplinary artist who grapples with the mighty and the mundane through his bold and modern work.

The artist Bora Akinciturk, Kayhan Kaygusuz

“What inspires your work?” I ask the heavily tattooed and artfully grotty Bora Akinciturk.

“Being alive,” he smiles. What might seem like a non-answer when compared to the direct and feverish imagery which riddles his work makes more sense when it’s taken out of isolation. Akinciturk’s work – be it in oil paint, sculpture, or installation – gives form to both the mundane and the existential misery of today’s society.

Akinciturk hails from Turkey and works mainly from London. He came onto CONCRETE’s radar through our good friends at SCREW gallery (following his show Group Ego Death Yoga and Meditation at their space) – and we’ve been watching with fascination since.

Group Ego Death Yoga and Meditation at Screw Gallery Jan-Feb 2022. Image is courtesy of Screw Gallery.

“I was very happy with that show,” Akinciturk says. He doesn’t look 40, and his paintings of Jim Carrey and hentai don’t scream ‘middle age,’ either. “I’m always happy to show for a younger and engaged art audience, and that was the case with the show at Screw,” the artist adds.

Considering Akinciturk tries to “make new work as much as possible,” where do we start when attempting to summarise his practice meaningfully? Probably with reference to t’internet. A once green and pleasant land, now the internet hurls a content blitzkrieg of news, sex, humour, misery, shock and adverts at the consumer all the time and without hierarchy. Akinciturk collates the debris of these popular and internet cultures and gives them form in his work.

Talk of ‘high culture’ and ‘low culture’ feels antiquated now. As everything is everything and the falcon cannot see the falconer, Akinciturk digests this to form work indicative of a society at its wits’ end. This is art for 2022 – a year of excess following the coronavirus. Paintings, rugs, sculptures, he does it all, forming a dislocated world view which (as Frieze said) culminates in ‘physical traces of an individual browser history’.

As such, Akinciturk’s work is often typified by overlaid images from clashing sources. Take Deniz Belendir (2019). Over a Rothko-red background lies an organic shape (is it a rock? A turd? An alien face?) over which lays white doodles on top of which stands an anime girl with a luxurious fur tail. The work makes sense visually, but its references may appear scattered. This is entirely deliberate.

Deniz Belendir, 2019, oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist and Piveneli Gallery.

Art is always defined by its cultural context, and the context which surrounds Akinciturk’s work is the internet. Our lives are no longer digital or real, they are a combination of both, and the digital is increasingly winning this tug of war. “I’ve been online for a long time, surfing the internet, looking at images,” Akinciturk tells me, when I pry further about his knack for three dimensionalising the disorientating and constant nature of the online sphere. ”I think it comes naturally with being online so much, the outcome is something relatable and direct; like content from a shitpost account on some social media platform.” ‘Shitposting,’ for the uninitiated, is defined by Urban Dictionary as online posts with the ‘sole purpose to confuse, provoke, entertain or evoke an unproductive reaction’ with ‘little to no sincere’ substance.

Shitposting is probably the operative term. However, it would be foolish to reduce Akinciturk’s work to mere one liners. The frenzied nature some of his works exhibit are a meditation on representation – of multiple aesthetics and feelings supplanted on top of one another. Take his 2018 installation I’m So Happy Because as an example. Inside a tent is a television playing superficially random clips, an unhappy painting of what looks like a bar fight in Valhalla, and the recognisable debris of a bedroom – old water bottles, underwear, and cigarette butts. Unlike Tracey Emin’s comparable My Bed, Akinciturk’s work may provoke disgust at first. Emin’s famous work is likely to evoke pity and understanding almost immediately due to the recognisability of the poor mental state of this bed’s proprietor. I’m So Happy Because on the other hand could as much be the bedroom of a 2018 Kevin the Teenager as it could be of many broke creatives.

I’m So Happy Because, 2019, installation, courtesy of the artist and Piveneli Gallery.

The impact is that Akinciturk’s work can be read as something of a cipher for the age of confusion and instability which befuddles millennials and Gen Zs alike. As such, the artist’s work is based on the visuality of the internet. Ancient symbols, memes, and pop culture references all jostle for space as Akinciturk assembles them as equally important components within his compositions. “Sometimes while I’m watching something on my laptop I’ll pause it and take a screenshot to use for a painting. Sometimes an idea for a painting pops into my head, and sometimes I make most of the painting on photoshop, then I paint that final image onto a canvas,” Akinciturk describes.

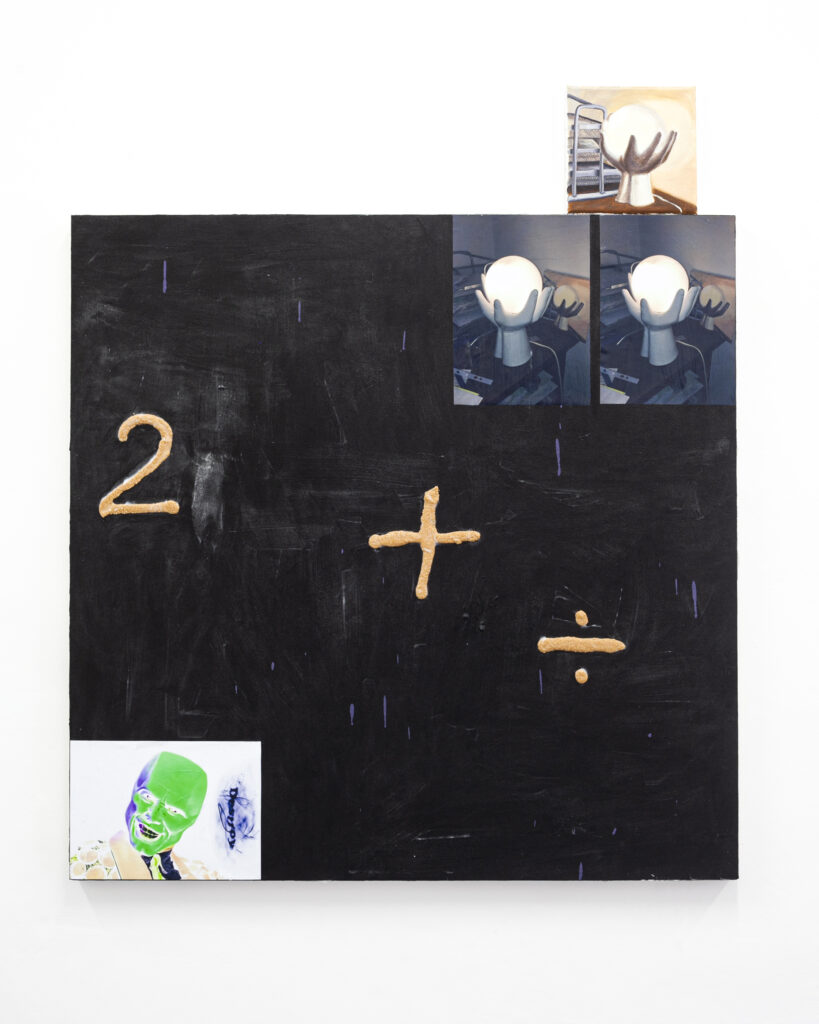

One repeating image in his work which I keep returning to is of Jim Carrey. The actor in his ‘The Mask’ role crops up multiple times in a series of paintings from this year. “I wanted that series of paintings to relate to each other the way people going to the same yoga class relate to each other,” Akinciturk says cryptically. “‘The Mask’ film has a similar situation going on as the mask turns the wearer into the mask’s own cartoon character with super powers, while still containing the original attributes of the person wearing the mask. That made me think that the image of Jim Carrey as ‘The Mask’ would make a good repetitive image to relate the paintings together the way I wanted.”

2-X├A, 2022, acrylic inkjet print on glossy paper, texture gel, glossy acrylic medium on canvas with 15×15 cm oil on canvas painting, courtesy of the artist and Screw Gallery.

While it is the visual base for much of Akinciturk’s work, the internet is hardly an aesthetic creation. What does it mean that instead of shying away from it Akinciturk confronts it head on? It is a refreshing change from other contemporary painters’ use of the medium. Instead of looking back, Akinciturk’s work is progressive – absorbing collateral imagery from the digital age and preserving it as a strange sort of time capsule for the very now. “Do you feel apathetic?” I say. There is a pause.

“Sometimes I feel indifferent,” is his reply.

The Western Marriage Company, 2020, oil on canvas, courtesy of the artist and The Residence Gallery.

So is modern life rubbish? Not necessarily. The internet contains almost as many facets and emotions as the human condition. Akinciturk relishes the gratification of “finishing a painting and liking it,” and appears more driven by the making and sharing of work than by other forms of remuneration. Moreover, when asked what is often one of the more revealing CONCRETE interview questions regarding time travel, Akinciturk responds; “I think I’d go to London or Istanbul in the future – maybe to 3022, or something”. I wasn’t expecting this answer considering the indicting quality his works may show.

“You wouldn’t go backward?” I ask.

“No way! That’s all happened already,” Akinciturk smiles again.

All images are property of the artist and stated galleries. You can keep up to date with Akinciturk via his instagram, here.