Taking into consideration all his mediums of practice, the filmmaker, artist, and gay rights activist is celebrated through this timeline of his multifaceted career at the Manchester Art Gallery.

The Derek Jarman Protest! exhibition is a retrospective of the artist’s career as he changed and experimented with different mediums. As such, the exhibition includes paintings, films, mixed media works, and objects from Jarman’s life. The Manchester Art Gallery has also given Jez Dolan (the Salford based artist working from Paradise Works) a residency at the gallery where he will work with a number of queer artists based in the North West to explore Jarman’s legacy. Plus, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence will canonise performance artist David Hoyle as part of the exhibition. Finally, a green space inspired by Jarman’s Prospect Cottage garden has been installed at the front of the gallery by a group of ‘green-fingered LGBT+ over 50s’ with the help of artist Juliet Davis-Dufayard. The exhibition is only temporary, but Jarman’s legacy is permanent, so says Manchester Art Gallery.

Warm-hearted additions aside, how does the art hold up? Very well, but this is no easy feat. Meaningfully showcasing a multidisciplinary career of 30+ years with sufficient depth is not a simple task. Thankfully, the video-based portion of his career is spoken for, as HOME cinema is showing all the films he is credited as directing. With his films sidelined, the exhibition is able to give the focus to his fine art. Spanning three large rooms, the show includes his work made as a student, his geometric work (which received critical acclaim and was shown in the 1967 Tate Young Contemporaries show), his set design, and finally his overtly political work made in the early 90s.

The exhibition commences with Queer (1992). Alone against a dark blue wall, Queer is a huge, bright red, canvas with ‘QUEER’ boldly scratched into it. This is one of Jarman’s Slogan Paintings series. These works were made at the end of his career and with the help of studio assistants because Jarman’s health had deteriorated so much due to AIDS related illness. Its appearance at the beginning of the show foreshadows the difficulty afflicting Jarman at the end of his life, giving the exhibition a bitter sweetness as the vitality of his earlier work withered. Regardless of prior knowledge of Jarman, the work is a fitting opening to the show in that it is (as its title points out) unapologetically queer. At risk of saying this opening is what Jarman would have wanted, I’d imagine it’s what he would have wanted. During the Thatcher administration and after his HIV diagnosis, Jarman’s sexuality was further politicised. To be public in his sexuality and his illness remains an act of bravery, defiance and integrity.

Beyond Queer, the exhibition follows a chronological format. His early, more figurative paintings completed at the Slade School of Art take in multiple influences which result in work which is referential whilst maintaining its own perspective. No better is this shown than in his Untitled Landscape (1961). It’s thoughtful and dark, quiet like much of his early work – a far cry from the flamboyance of the Alternative Miss World contests Jarman attended in the 1970s. These periods could well be segments of two totally different artists’ careers. Resultantly, the viewer can understand Jarman as someone exciting enough to garner the title “London’s Andy Warhol,” and who was introspective enough to paint quiet self-portraits, feel a kinship with Wyndham Lewis, and garden in solitude.

It should be clear, then, that the critical asset the Manchester Art Gallery sees in Jarman is his capacity for transformation. While his values and dedication to the work remained the same, his interests changed through his career. Jarman was probably too old to pogo with the rest of them in 1976, but he shot the first ever Sex Pistols footage and directed Jubilee, a feature film which remains a memento of the punk moment, and a clip of which plays in the exhibition. This attests to Jarman’s capacity for reinvention and his consistent relevance. What makes Jarman worthy of a garden, a film season, a retrospective and whatever Jez Dolan gets up to, is impact on British cinema. This is indicated by his success straddling the arenas of art and popular culture. This is not easily done, and he did so without dumbing down his work or bending to the will of critics.

To me, there are two stand outs in this exhibition: Jarman’s Black Paintings series and his 1993 film, Blue. The Black Paintings are a retaliation to homophobia upheld by legislation under Thatcher. Suitably, these works all feature a black background, seemingly casting their inhabitants into the shadows. Golden, sexualised bodies mingle in the night time, adorned with the decoration of white ejaculate and abstract red decoration. The works are also referenced later with Jarman’s Assemblages, the works made at Prospect Cottage which he bought in 1987. An especially interesting assemblage is Pyjamas (1987); a thickly painted black canvas embedded with condoms and finished with a glass overlay. ‘He’ll be wearing pink pyjamas when he comes,’ is wryly scratched into the work.

Blue plays in it’s entirety on loop at the exhibition.

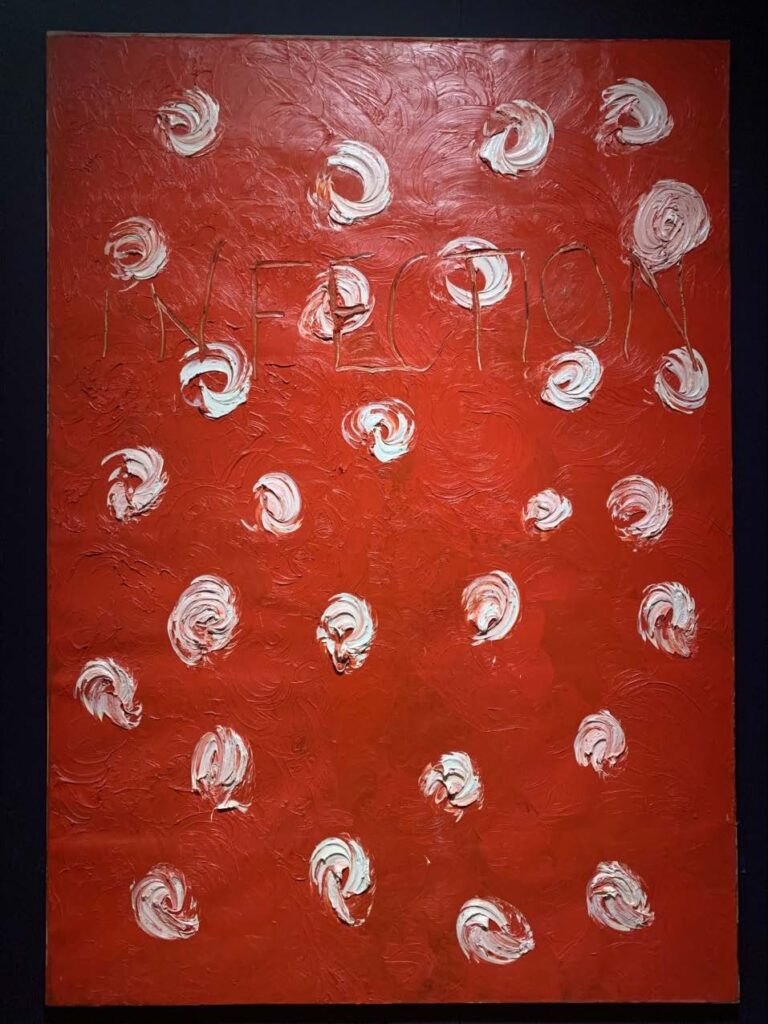

Blue is very moving. In its own room, Jarman’s final film runs in its entirety on loop. By this time, AIDS-related illness had damaged Jarman’s health significantly. Symptoms included flashes of blue light obscuring his vision. Consequently, Blue consists of a single static shot of International Klein Blue accompanied by music and voiceover. The film meditates on sound and colour, the static blue image grounding the viewer in the room through its hypnotic consistency which forces the ears to do the visualising. Blue is poetic and reminiscent, somewhere between stream of consciousness and fly-on-the-wall documentary of Jarman as a patient. When the viewer comes out of Blue dizzy, the garish red of Pill Pusher (1993) and Infection (1993) are a bleak, ugly shock. This is curation done properly.

Infection, Derek Jarman, 1993.

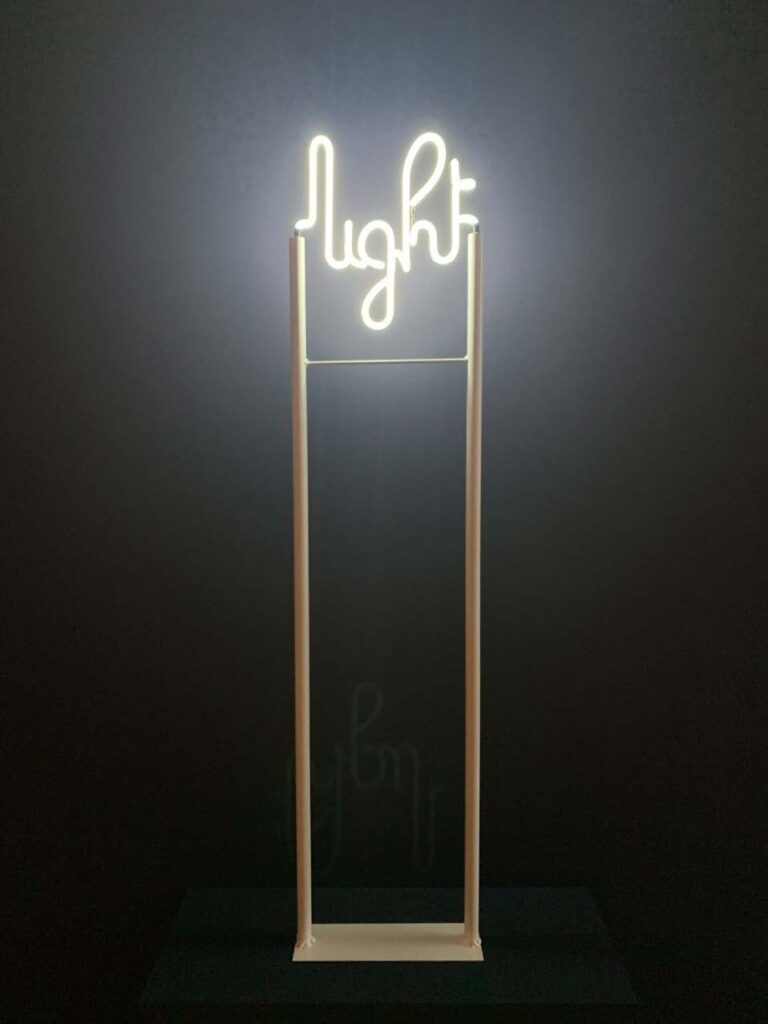

After looking at the Slogan Paintings series and the penultimate work shown, One Day’s Medication (1993), it would be easy to leave Protest! merely feeling sad that such a talented and innovative artist’s life was cut short. After the Slogan Paintings, a video of Jarman guiding a film crew and visitors around his installation at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow plays. Jarman tells the film crew that he hopes one day people will laugh that an exhibition celebrating homosexuality had to happen. To hear Jarman talk, after walking through his career, feels brilliant. My suspicions that Jarman was a terrific person to know (aroused by cuttings of his interview in Warhol’s Interview magazine and images of him at the Alternative Miss World events) are confirmed. He tells the film crew he buys the magazine the same Jehovah’s Witnesses peddle at his door every week, just to “stay in touch,” despite being a staunch atheist. He is eloquent, personable and more interested in the opinions of the visitors than his own. However, the arrangement of the exhibition evokes a more contemplative conclusion. The final work shown is the gallery’s remake of Jarman’s 1970 neon glass tube bent to spell ‘light’. The work is clearly the offspring of the Bauhaus movement, combining art and utility. As Queer foreshadows Jarman’s premature death, Light conjures images of Jarman in his prime, as the energetic and daring artist and socialite of the 70s. It’s hard to resist forming a mental picture of Jarman as a gorgeous man, unfairly taken too early.

The Manchester Art Gallery’s exact copy of Jarman’s 1970s Light sculpture.

The first image is a 1992 detail of Queer (1992) courtesy of the Estate of Derek Jarman. The exhibition is free and runs until April 10th. The HOME cinema series includes Blue, Jubilee and The Tempest.