CONCRETE seeks to provide a simple yet detailed explanation to the question that is keeping the traditional arts up at night. Read on to not only find out who’s winning and who’s losing in the non-fungible arena, but also why the winners don’t want you to know how NFTs really work.

CROSSROADS, BEEPLE, (2020).

What was once a gulf between real and digital is lessening. After a year indoors, the digital is the real. With this in mind, interest in NFTs is very much a product of our times, and – against the backdrop of Covid – NFTs have had a great 18 months. In 2021 alone, Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s first tweet was sold as an NFT for $2 million, Lindsay Lohan’s anthropomorphised dog-self NFT was met with anger from the furry community for cultural appropriation (Lohan herself is not a furry), Kings of Leon released an NFT album, and NFT artist Pak’s Sotheby’s sale yielded a total of $16,825,999 in their April auction. Novelty headlines indeed. Respite from news about climate crises and covid flare ups, I suppose. It’s sort of fun to oscillate between feelings of guilt (I am part of the climate problem) and annoyance (Kings of Leon NFT album).

Funny or not, these headlines have done little to dissolve the confusion surrounding non-fungible tokens outside of the NFT community. This is not due to the general public’s ignorance – far from it. It appears that the people who are benefitting the most from the rise of the NFT have mistaken an advancement in technology for an advancement in art – putting the uninitiated into a category of luddites, naysayers, gatekeepers and unimaginatives. NFTs should not be written off, but before this silliness goes any further the factors contributing to their rise need to be gone through with a fine tooth comb.

NFTs are a new class of financial asset. Jot that down, because the digital art NFTs are linked to is not new, and that will be important later. A non-fungible token is a certificate of ownership uploaded to the blockchain which is then tethered to a work of art. The certificate of ownership guarantees the authenticity of the artwork and the owner’s immutable ownership of the work of art it is linked to. This detail often feels glossed over, but it’s critical – especially given the hype and expectation surrounding NFTs that casts them as a fixall for the problems which riddle the art market.

So we are all on the same page, some description of the functions of NFTs is needed. There are NFT artists and there are NFT projects. NFT artists’ art goes to market in a comparable fashion to traditional fine art. It is uploaded to a marketplace (OpenSea is the largest) and then it is bid on. NFT “labs” or “projects,” on the other hand, create a collection of unique avatars which are sold with NFTs, each representing a share in an upcoming scheme. Projects are either in real life or in the metaverse. For instance, if you buy a Bored Ape Yacht Club Bored Ape you are granted membership and access to The Bathroom, a community graffiti board which BAYC’s website homepage predicts will be ‘full of dicks’. Similarly to BAYC, NFT projects GOATz, Dream Babes and TipsyTiger Club encourage a person to buy an avatar using the corresponding cryptocurrency, most often Ethereum (ETH). This grants the buyer benefits in different forms. There are: additional accesses (for example, the ability to take part in thrilling GOATz competitions and community projects); entitlement to royalties (a bonus to playing as a dating app CEO in the Dream Babes game); or dividends in a pending product (TipsyTiger Club’s delicious hard seltzer). Avatars selling alcohol, a Second Life-esque dating game, cartoon monkeys looking bored – none of the above sound very aesthetic to me.

What emerges is a picture of the NFT boom as a series of separate companies (more artfully referred to as “projects”) capitalising on the good feeling many have-a-go investors felt during the GameStop bubble. The blockchain is a decentralised platform which cryptocurrency transactions are recorded on, meaning there is no central bank and no singular owner of an NFT project, only shares and divided ownership. Very equal… if you look past the soaring prices of NFTs. This model essentially sees the NFT function as part-joining fee for the corresponding community, part-cash investment in the corresponding project. The investor receives a share in the project (a perk of decentralisation) and becomes the proud owner of a highly desirable asset class. The NFT project gets money from supporters and the supporters get a digital asset. However, just like there is no guarantee that NFTs will supersede the painted canvas in the future, there is no guarantee that NFTs will be worth something in five years.

Nevermind – perhaps NFT art for art’s sake is better. Some of the most successful NFT artists in 2022 are Mad Dog Jones, XCOPY and BEEPLE. Mad Dog Jones seems to concern himself mainly with more cynical versions of the mass-produced illustration prints I remember covering BA students’ university rooms. Tokyo-ish neon signs, lampposts with stickers screaming ‘WHAT IS YOUR DESTINY?’, deserted laundrettes and back alleys. In truth, they would make nice screensavers.

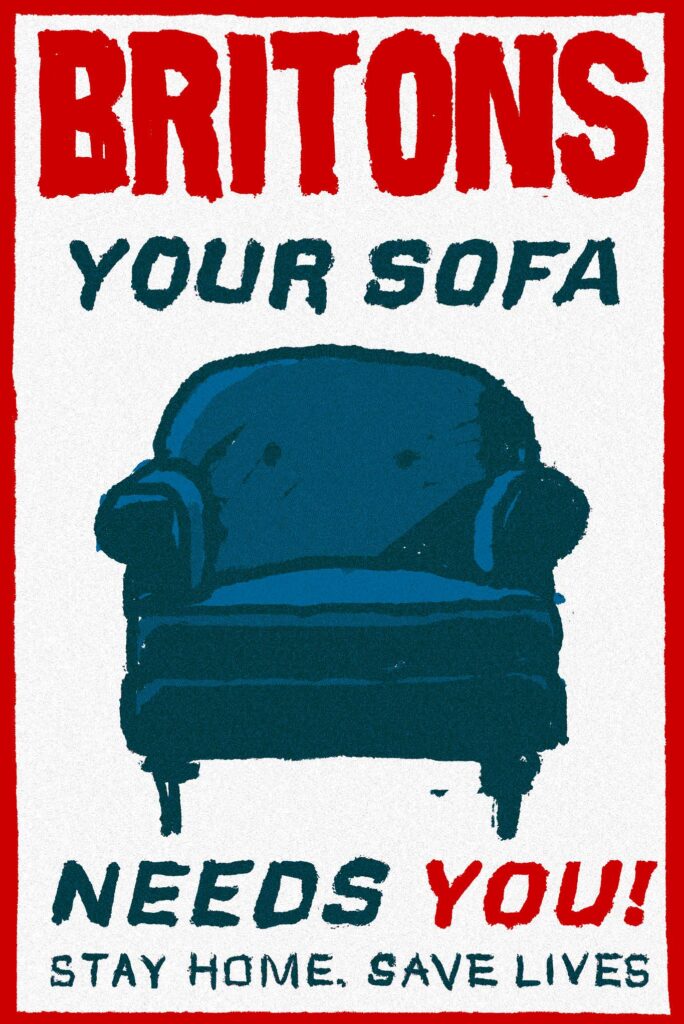

XCOPY is a London-based crypto artist. His work Right Click and Save As guy (2018) was bought by Cozomo De’Medici (who may or may not be Snoop Dogg) in 2021. His works are either images or GIFs and they tend to have witty titles. These include Your time won’t come., Instabags, BANGERS AND CRASH, and DANKRUPT. There appear to be two distinct styles, one consisting of flat, scribbly, digital sketches drawing on dystopian and gothic imagery, and another which is purely geometric and pixelated. One that stood out to me (perhaps because it isn’t so busy looking) is Britons (2020). This work is a GIF, albeit only signalled by the fuzzing pixels that it is made up of. Clever, though – you can’t screenshot a gif. In large capital letters the work screams, ‘BRITONS YOUR SOFA NEEDS YOU! STAY HOME, SAVE LIVES’. The work alludes to the Covid-19 lockdown and references the famous Lord Kitchener poster appealing wartime Britons to join the army. Kitchener is replaced with an uncomfortable looking armchair. That the shelf life of NFTs is already debatable, to make Covid-based NFT art is downright perilous. Who’ll look at that in five years?

BRITONS, XCOPY, (2020).

XCOPY’s portfolio also touches on other issues of our day. Broken scales and an American flag are ablaze in his 2020 GIF, BROKEN, and a gloomy gentleman takes a final selfie with the grim reaper in Last Selfie (2019). A personal favourite is State of Us (blue), 2019, in which a robot seen through a blinkered lens looks so intently into a smartphone he shoots blue laser beams from his eyes. The telescopic lens expands to reveal the robot is on a smartphone screen himself and the smartphone is being held by an anonymous pitch black hand! It feels a little obvious, and the works’ lack of personal perspective is damning. Like much NFT art, XCOPY’s work looks like a dispirited version of a friendlier but equally marketable predecessor, Corporate Memphis, the disparagingly named illustration style that dominates Big Tech. The similarity is unsettling, especially because the decentralised blockchain is supposed to free us from the shackles of the pervasive, omniscient forces of fintech.

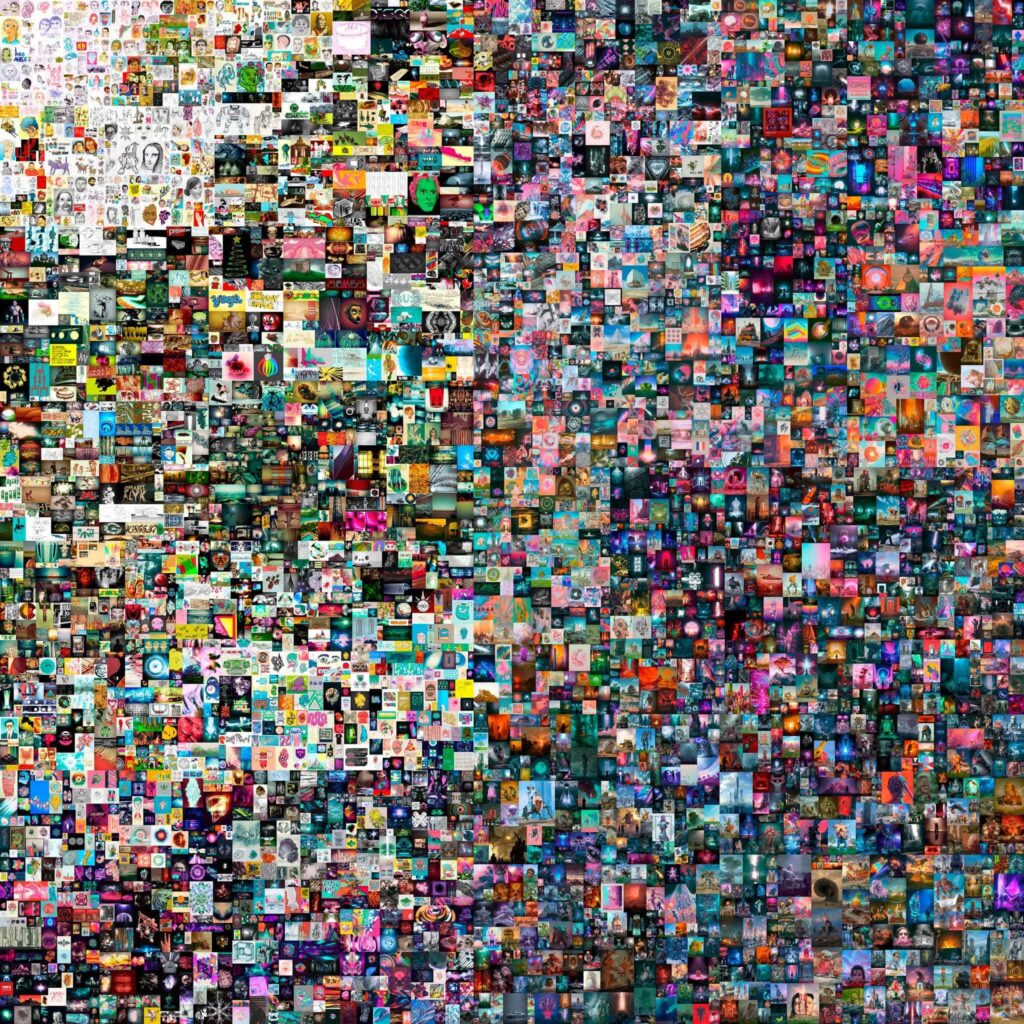

Mike Winkelmann, known as Beeple, sold Everydays: The First 5000 Days for $69.3 million at Christie’s in 2021. Until Pak’s The Merge beat it on December 2nd, the associated token of the work was the most expensive NFT in the world. Beeple is one of the most expensive living artists to own work by. The First 5000 Days comprises every single new work of art Winkelmann made daily over 13 years in one large composite image. It was tokenised and attached to a non-fungible token which was sold at Christie’s. The First 5000 Days has been described as a timeline of Beeple’s artistic development and of US politics. The viewer can see Beeple’s changing style; the top left of the image is dominated by what looks like pencil portraits, and by the bottom right of the image (presumably Beeple’s most recent works) the images are entirely made up of digital and more dystopian, pictures. A large half-Michael Jackson, half-Kim Jong Il icon is split in half revealing a shared brain. A woman with a Pikachu helmet and bare breasts marches alongside hundreds of tiny soldiers in a futuristic world. This type of figurative imagery in art feels akin to lazy zombie movies – it relies on the viewer’s understanding of an imaginary world with specific conventions (the undead feasting on the living, cities turned to rubble) which does not require much further explanation because the set up (humanity has gone “too far”) has been seen so many times before. For a deep dive into the visual qualities and connotations of Everydays, I recommend ArtNews’ national art critic Ben Davis’ ‘I Looked Through All 5,000 Images in Beeple’s $69 Million Magnum Opus’ article.

EVERYDAYS: The First 500 Days, BEEPLE, (2021).

Beside eye watering prices, the trait Mad Dog Jones, BEEPLE and XCOPY art is unified through its lack of position. It gestures to a subject without offering a perspective on it. Technical ability, coherence, and means are of little interest to me, but this directionlessness is tantamount to laziness. CROSSROADS by Beeple is another example of this sort of brightly coloured inertia. CROSSROADS takes in elements of mass culture and gestures to the political climate. A large, naked, and defaced Trump corpse lies by a tree in front of a rainbow and behind a street where normal sized people walk. A blue bird lands on Trump’s back and a speech bubble with a clown emoji appears. The image points to things – the dead Trump is a stand-in for the end of the Trump administration, the blue bird on his back a stand-in for Twitter, and the people represent people. Art historian Monica Belevan tweeted that ‘political art is agonistic. This is post-political,’ because ‘the market has no problem metabolising it: there is no resistance to build if there’s no conflict’. Offering no transgression or perspective, the traits that limit a critical response to this work help it to market.

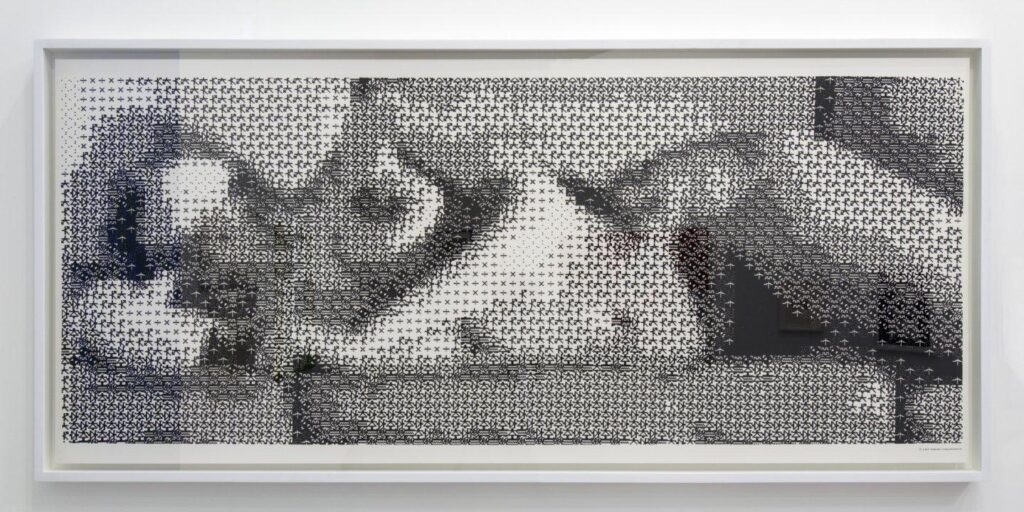

Lack of position in NFT art is mirrored in disinterest in digital art’s history and is telling of indifference to art. There is a narrative surrounding NFTs which implies that they are a new class of art object. Digital art is not new by any stretch of the imagination, and neither is the anxiety about the aesthetic status of a digital-made object which critics of NFTs have displayed. In 1966 the first digital nude was made. Studies in Perception was created by researchers Kenneth Knowlton and Leon Harmon at Bell Labs. A photograph of dancer Deborah Hay was remade as a bitmap mosaic using a program developed by Knowlton and Harmon. The work takes into account its form as a digitally made image. Where the photograph had greyscale to indicate three dimensionality, the resulting computer generated work has programme symbols. The viewer can easily see the female form through the use of these symbols because the human brain can interpret the abstract symbols piled on top of each other as areas of tonal value and the more sparsely populated parts of the image as plains of skin. Computer symbols become the paint – as the title suggests – questioning the limits of human perception. Similarly, by depicting one of art history’s favourite subjects, the image invites the viewer to consider its aesthetic status. The work is innovative, self-reflexive and aesthetically pleasing. Don’t just take my word for it, the image was printed on 12 feet wide paper and ended up in Robert Rauschenberg’s loft.

Studies in Perception, Kenneth Knowlton and Leon Harmon, (1966).

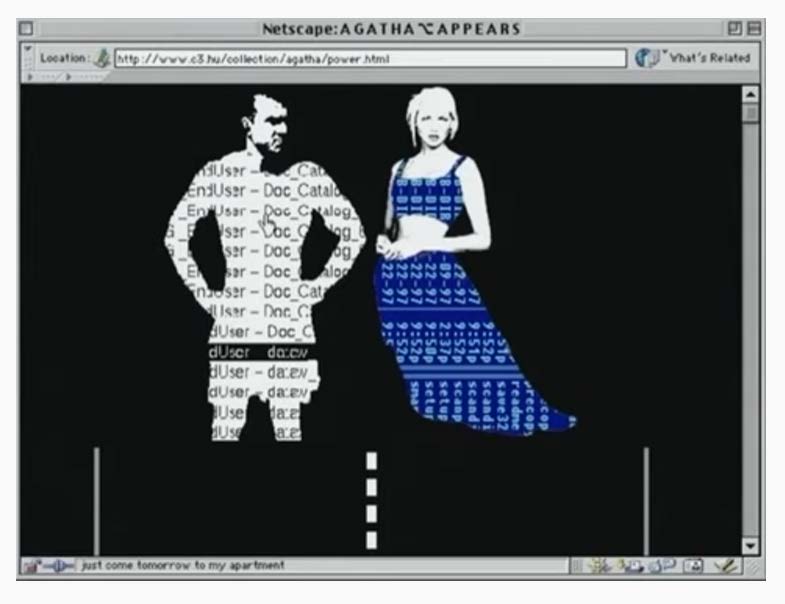

Thirty years later, Net Art emerged in the 1990s, pioneered by Olia Lialina. Her 1997 short film Agatha Appears sees a digital Agatha meet a digital sailor inside an internet window, soundtracked by ‘Dei Tuoi Figli La Madre (Medea)’. The video takes place within the internet; Agatha and the sailor inhabit a webpage (or a “Netscape,” as Lialina’s work calls it), and below them is a grey bar at the bottom of the screen with icons alluding to different computer softwares. The sailor asks Agatha, “have u heard about the INTERNET?” and tries to help her teleport through it, but fails because there is a problem with the connection. Nevertheless, the pair agree to meet at the railway station the next day. The sailor tells Agatha that “to understand the net you must be inside” it. Like Knowlton and Harmon’s printout, Agatha Appears is aware of its form – a video made on the internet using features of the internet – and its form’s context. Lialina’s video alludes to the opportunity and excitement of the internet as well as its drawbacks. The sailor is excited, but Agatha is more sceptical when the sailor tells her the internet is about “new philosophy”. Besides, as the pair find out, the connection doesn’t always work. Referring to and fictionalising stereotypes of the internet in an internet made video shows that Lialiana recognises the context of art on the internet and with her artistic response she offers a dose of whimsy and cynicism. Plus, like Studies in Perception, the work is still of note today. It is indicative of attitudes toward the internet at the time, and remains interesting to look at.

Agatha Appears, Olia Lialina, 1997.

The disparity between the rich visual qualities and webs of references of these two works and works by NFT rockstar BEEPLE’s is vast. Everydays: The First 5000 Days was bought by Vignesh Sundaresan and Anand Venkateswaran. Sundaresan and Venkateswaran took to metapurser.com to explain their purchase; the pair wrote that the point of the purchase was to show that ‘crypto was an equalising power between the West and the Rest, and that the global south was rising’. It would seem that even for people willing to part with 60 million dollars for NFT art it isn’t about the art. That Winkelmann has found such success is indicative of the convergence of neoliberal policy, rising populism and the merging of the digital life with the real life. As state funding for the arts in America and Britain has withered, cross pollination between images used to sell something and images made for the sake of images have complicated matters. Art functions as window dressing in advertisement, offering a more subtle and visually appealing approach than a hard sell. This is duplicitous, but I could (for argument’s sake) make peace with it if the process didn’t contaminate art as well. That the simplicity of meaning and compliance with the status quo of advertising has infected art, the bastion of freedom of expression and creative singularity, can be seen in Beeple’s work. Beeple’s work – like an advert – is easily comprehensible. The work’s subject is clear, but there is no angle and there is no combative antagonism. It is ‘without insight or criticality,’ laments Dean Kissick. Part of this simplification is due to the convergence of culture. The line between art and commodity has further blurred.

The convergence of shopping cultures has worsened the intermingling of art and advertisement. Collectibles are sold in the same space as traditional fine art is, and sometimes even in the same auctions. That disparate items – sneakers, comics, jewellery, and traditional fine art – are being sold in the same space and even side by side suggests a confluence of these markets. What’s more, “drop” culture in retail – luxury or otherwise – creates its own artificial scarcity and generates interest in brands like Supreme and Yeezy. This strategy can be seen within the sale of NFTs. NFT platforms like OpenSea, Magic Eden and Solsea all have multiple drops scheduled with no sign of slowing down. This positions NFT art somewhere between art and luxury objects. They are auctioned like traditional fine art, and “drop” like the latest Nike trainers.

Furthermore, against the backdrop of our neoliberal age, populism has surged in the West. Much like Trump’s anti-establishment persona is as leftist as fox hunting, the rise of NFTs represents a very specific type of anti-establishment reaction which opposes the more usual variety of transgression that traditional fine art fosters. Take Colborn Bell, crypto curator and collector, as an example. Bell founded the Museum of Crypto Art and has a background in finance. Bell described how he did as much investment banking as he ‘could take’ and then looked for something more fulfilling.⁵ That many NFT artists and practitioners come from a financial background and go into the art form closest to fintech makes a lot of sense. Yet it pays to mention that this is not the conventional art “way”; art history famously prefers progressiveness to conservatism. Somewhere along the way the NFT crowd has mistaken anti-establishment libertarianism for radicalism.

Part of the “NFT revolution” promise is that it will enable a decentralised art world without fusty institutions and snobbish experts. As the investments in NFT projects hide behind the purchase of a unique avatar, and these projects obscure investment in the blockchain, the ideology underpinning NFTs is hidden. Technology always has an ideology. Neil Postman’s Technopoly reads, ‘embedded in every tool is an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing,’ and this is what Marshall McLuhan meant by ‘the medium is the message’. What ideology does NFTs prop up? The blockchain is a peer-to-peer network without control from a single organisation or individual. Due to the influence of companies like Facebook, endangered privacy is a big issue, so it is understandable why the much-touted security of blockchain platforms is so attractive. Coupled with the growing desire for digital assets, decentralised currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum are tempting. What they offer, supposedly, is privacy and democracy.

The result of these factors – both long ranging like the withering of state funding and the more recent like the desire to own digital assets – is that the art attached to non-fungible tokens is incidental. As Brian Droitcour of Art in America writes, NFTs – under the guise of supporting artists working in a fledgling form – offer an investment in tech with ‘a veneer’ of investment in the arts.

This is the actuality of the rise of NFTs as valuable assets. If this is not enough to convince you of the duplicitous and concerning marketing which is positioning NFTs as a “disruptive” alternative to the opaque art market it is worth comparing the current moment to previous so-called “revolutions” of recent history. At the 2021 NFT.NYC event, digital fashion customisation platform founder Enara Nazarova quoted leftist activist and writer Naomi Klein’s famous mantra, “there are no non-radical futures left”. Such euphoric hyperbole (Nazarova ended her speech with “to infinity and beyond!”) and neutered political catchphrases mirror a similar tech “revolution”. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron coined the ‘Californian Ideology’ term in 1995 with their essay of the same name. Barbrook and Cameron described it as ‘a mix of cybernetics, free market economics, and counter-culture libertarianism’. It has been ‘embraced by computer nerds, slacker students, 30-something capitalists, hip academics, futurist bureaucrats and even the President of the USA himself’.⁹ Somewhere, between rightwing avarice and leftwing respect for civil liberties, sits Silicon Valley, and, more recently, the NFT community.

If I had the money, I would buy an NFT and flip it. If you have the money I’d advise you to do the same. But, at the behest of those who are envisioning NFTs as an art “revolution,” the truth is that the rise of NFTs is driven by investment in technology for profit. With this in mind, take some advice that’s so old it’s out of copyright: buy an artwork because you love it, not to sell it. There is simply no way to know which way the market will go in five years, nevermind fifty. NFTs are valuable right now, but that doesn’t mean the corresponding image will have lasting value, and it certainly doesn’t mean that they are changing the art world.

I opened this article with a firm declaration that the general public is not stupid. We are often bemused – but that makes a lot of sense when the news constantly seems to get stranger. Not many people outside of the art bubble (and even most of us don’t know, either) feel they know enough about NFTs to have an opinion… or so I thought. Although only speaking anecdotally, I have noticed a shift in online mockery of NFTs. What appeared to be confined to the more humorous and surreal niche of comedy twitter has spread. The irritation and disinterest fuelling jokes and memes about how art robbery has changed from daring heists to clicking Ctrl+C has saturated Instagram. I was delighted to see that on the @highsnobiety (the streetwear blog turned Generation Z’s Rolling Stone) instagram, a recent post on NFTs’ most liked comment simply read, ‘I don’t fuckin care, stop posting about nft’.

All images are property of the artists.

Monica Belevan, @LapsusLima on Twitter.

Studies in Perception, V&A collections.

Vignesh Sundaresan and Anand Venkateswaran, Metakovan and Twobadour, ‘NFTs: The First

5000 Beeples,’ The Metapurser.

Dean Kissick, ‘The Downward Spiral: Popular Things,’ Spike.

Colborn Bell Interview, Artnet.

Neil Postman, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology.

Brian Droitcour, ‘How to Look at NFTs,’ Sub Stack

Ben Davis, ‘Inside the NFT Rush: Entrepreneurs Promise NFTs will Destroy Gatekeepers, While

Jockeying to Become the New Gatekeepers,’ Artnet News.

Richard Barbook and Andy Cameron, ‘The Californian Ideology,’ Mute, Volume 1 No. 3.