Off the back of his latest show OK! Cherub! at the Bluecoat in Liverpool, CONCRETE spoke to Bruce Asbestos and reflected on the role of the artist in our time.

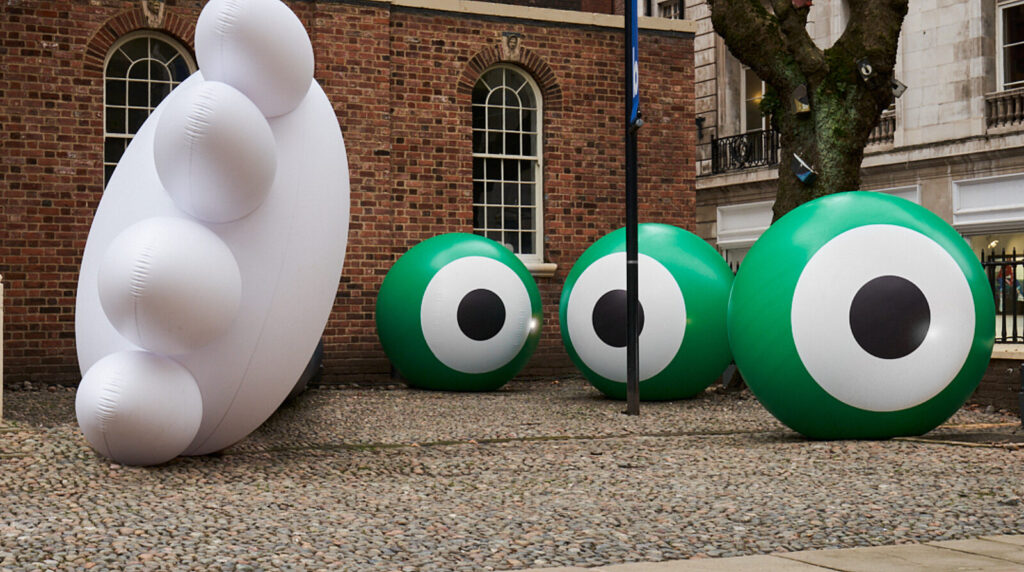

OK! Cherub! at the Bluecoat in Liverpool. Image by Rob Battersby.

The job spec for an artist has changed over the centuries. If we start at the very beginning, the Palaeolithic artisté was tasked with documenting the important moments, give or take his own creative flair and desire for extra flourishes (why is there a square depicted in the Lascaux Caves, for example?). The importance of documenting events – or documenting how events should have played out – was upheld through Classical Antiquity and into the Middle Ages. Of course, within the bracket of documentation comes other purposes, like practising faith or forming part of a cultural tradition or ceremony. But as the drum of history beat on, art took on other responsibilities.

With Michelangelo and later Leonardo da Vinci as the crème de la crème, the Renaissance expanded art’s MO. Da Vinci’s technological ingenuity made him a successful painter and led him to make critical discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology and optics. Da Vinci was watched by Venetians with fascination. He was lauded in society as a visionary and a noble. Similar, one might say, to our contemporary interest in Elon Musk. Like Da Vinci, Musk uses the latest technology and accumulated knowledge of past developments to achieve the previously unachievable. While his business ventures have been criticised for all manner of reasons (and rightly so, a ‘fitbit for your skull’ doesn’t sound that tempting), we watch Musk intently.

Musk doesn’t paint, or even put a jumble of found objects on a white cube plinth. However, if da Vinci’s methods and significance can be compared to Musk in our time, it suggests that the visual art’s mantle has changed. No longer is he required as a visionary comparable to a scientist. This begs the question – what role do visual artists play in 2022, if the traditional role of the artist as a chronicler has become outdated?

Bruce Asbestos provides one answer. Asbestos is a multidisciplinary artist based in Nottingham. His work churns folklore with popular culture through performance, sculpture and fashion using cutting edge digital technology. Unsatisfied to bury his work in small commercial galleries in London, Asbestos’ work is firmly in the public domain. On his own volition, Asbestos likens his artistic process to that of witches brewing a potion. “I was starting to think about things on a conceptual scale as being like a soup – a soup of ideas and images,” Asbestos tells me in regard to his latest show.

OK! Cherub!, image by Rob Battersby.

“The Eye of Newt is a direct reference to Shakespeare,” Asbestos says, of his bright green eye motif which has been used in digital and sculptural contexts, including at the Bluecoat. “Shakespeare is the best that British can be in a way; this fantastic literature that changed the world and made new words. From here, I started thinking about the symbolism of the witches in Macbeth,” Asbestos describes. The Eye of Newt symbol has taken different forms. It first debuted on the artist’s instagram as a digital render, but has since been three dimensionalised in the form of a giant inflatable sculpture. This adds an extra layer to Asbestos’ practice. Art objects and performances are rendered in physical or digital realms, and – most innovatively – in a composition of both the real and the digital.

The Bruce Asbestos brand – as ArtReview pointed out – is one of ‘unmistakable visual identity’. Describing his own’ unique pictorial language in regard to OK! Cherub! (his most recent exhibition) Asbestos says, “I was thinking about new symbols, new images, and new references to build a crew of icons that I could then deploy as art works”. Equipped with this idea soup, Asbestos then places his symbols in the public domain through performance, sculpture and fashion using digital means.

It’s a novel and compelling approach. Asbestos’ OK! Cherub! runs until June at the Bluecoat in Liverpool. It consists of three giant inflatable sculptures – a yellow worm representing Rest, a group of green frogspawn to represent Community, and a large cartoon arm representing Connection. The sculptures are bright and inviting. Marrying the grubby and the gooey with the clean and vivid aesthetics of Pop Art is a welcome innovation which differs from the digested and more predictable commercial applications of the form. Asbestos recounts visiting the park daily with his young son during lockdown and watching the frogspawn turn to frogs; “There’s something really magical and resetting about watching the process of something becoming alive, including how gooey and disgusting it is as well.”

OK! Cherub!, image by Rob Battersby.

“A lot of the inflatable sculptures came about, because I wanted to make a sculpture that size but I didn’t want to use massive amounts of material. Although they are plastic, they can be easily repaired, and they can be made into wallets and handbags and other things at the end of their lives. I wanted the scale, and the best way to get to scale is to have something that inflates. Plus, people warm to PVC, because it’s so wobbly. It’s a bouncy castle reference, if you like. I want people to enjoy the sculptures and I want the materials to tell people how to interact with the work. The sculptures at Bluecoat attract lots of people to them which I’m definitely keen on. It’s fine to stand near them, and to take a selfie, or whatever. That’s really important to me. When people engage with them too much it becomes a headache for the gallery showing it, but that’s the result of having something attractive to a lot of people,” Asbestos explains.

“When I looked into what the ‘eye of newt’ actually is, I found it’s much less sinister than it sounds – like how garam masala is a mixed bag of stuff, Eye of Newt is the same. It’s a very benign thing. I was interested in this way of describing something bad that actually isn’t menacing. It’s just soup ingredients. I guess I was trying to find a bag of imagery that I could use and deploy in multiple places and ways,” Asbestos recounts. The resulting Eye of Newt artwork is a watching-eye, observing the environment it is deployed in: the “first ingredient” in producing an alternative to the world’s post-Covid problems. By blowing up these most small and seemingly inconsequential creatures and imbuing them with the witchcraft of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Asbestos mysticises the mundane, and invites the viewer to celebrate prosaic.

It doesn’t stop there. Not only is the work positioned to facilitate the general public’s engagement with it, but Asbestos also pulls references from recognisable sources. This is a line any ‘art person’ has heard many times before. What makes Asbestos’ work more novel than a traffic cone in a gallery – although Asbestos confesses, “I probably have put a traffic cone in a gallery before” – is that he synthesises a wide range of sources and alters them to revoke their previous connotations to create his unique visual language. “It’s very important to me that these things come from a background of Britishness, in a way,” Asbestos clarifies, “I might reference a Kokeshi doll, which is a Japanese doll, and I still do that, but I feel like I’m trying to bring out a British Pop Art-ness that isn’t about red telephone boxes.”

A/W Collection 2019, Bruce Asbestos, image by David Severn.

“I was thinking about worms and earthiness, the Mediaeval, and grubbiness, and how that is maybe a British Pop Art in itself. I was putting all these references into a witches’ brew and thinking about artists as almost witches. I allowed myself to be quite wandering and meandering. I didn’t want to come out with concrete statements about this meaning that,” Asbestos maintains.

Asbestos’ mixing of British culture, levelling the icons it takes in as equal parts, by churning them into an ‘idea soup’ is the beginning of the process in refining the artwork. The artist makes it very clear that he wants to avoid the already culturally digested and well used motifs that Britishness often conjures. “I was thinking of anything pre-Beatles,” Asbestos states. “That sort of red telephone box iconography can function like a strange form of nationalism. There is a lot of stuff I don’t relate to and have nothing to do with. I don’t relate to the British flag. I don’t relate to the telephone boxes.” Asbestos has a point. British pride is a phrase with few positive connotations, from Brexit to Imperialism. He considers the question – what are the British symbols that I actually relate to? With this in mind, the development of earthy and Mediaeval references into unnaturally large and plastic forms suggests Asbestos’ flair for generating engagement. The viewer is invited to feel ownership over the work. “I was trying to look for images that didn’t remind me of colonialism. Trying to find symbols that are less dodgy, I guess,” Asbestos laughs; “Colonialism is suffocating. It’s not fun and pop”.

Pop being the operative word. Asbestos draws from Japanese, British and American Pop Art. His cultural jukebox mentality of taking in multiple references from multiple sources, either British or pan-European, is what makes Asbestos’ practice so interesting. Pop Art is loved the world over and is important. That being said, the phrase ‘too much of a good thing’ comes to mind. Its influence and visual strength do hold up 70 years later, despite the saturation of its style and imagery flooding into the thoroughly non-aesthetic arena of high street shops and Velvet Underground banana tattoos. What can be done that is new with an art form, when the mass culture and advertising imagery it utilises, has already been reclaimed by advertising and mass culture?

Look to Asbestos’ recent Cruise Collection 2021. This performance took place at Manchester’s Holden Gallery and in Microneme in Wuhan, China, last August. This digital catwalk combines real footage and digitally rendered clothes. Asbestos’ 2021 collection considers the power of cultural identity within a globalised visual culture and reinterprets pop culture icons from the perspective of an outsider. A model digitally rendered in fluorescent green and pink garb equipped with a giant crocodile head swaggers across the Holden Gallery. This is ‘Kroc’, a character alluding to McDonald’s tycoon Ray Kroc who expanded the fast food chain globally during his tenure as CEO. Asbestos utilises the Kroc character – with its connotations of the American company that is a symbol of the golden age of capitalism after WW2 – and puts him in a less pernicious format. No longer Ray Kroc, the single minded businessman, Asbestos’ Kroc is cuddly and friendly, closer to a sports mascot than a magnate. Other animal or inanimate characters are anthropomorphised into playful personas, too. A digitally rendered fried chicken person wearing a shirt and tie parades the space teasingly.

Still from Cruise Collection 2021.

These motifs typical of American excess which are almost universally recognisable are revoked of their connotations of globalisation and altered to provide fun and mischief. The world of Cruise Collection 2021 is a world in which the Asbestos brand is the only globalising power, and its only aim is to deploy its imagery world wide. “The traditional shape of the catwalk is actually really useful,” remarks Asbestos. The catwalk structure frames and contextualises the performance by giving each piece time to dominate the stage.

Mocking global capitalism in a way that gives whimsy is difficult. Satire is dark. Asbestos’ work is bright. To make jolly mascots of the hieroglyphs of a pervasive capitalist hegemony and to place the work firmly in the public domain both fulfils the work’s role as a catalyst for viewers on a personal or societal level and fits Asbestos’ witch analogy nicely. By putting art in such an open context as the free entry Bluecoat, it is art for the general public and it can incite action, from a conversation to more artworks. Like the witches who tell Macbeth he’ll be king, Asbestos’ art stirs the cultural pot, and he gives the work over to the public.

Catwalk of Bruce Asbestos X Juliana Sissions, 2019, imaage by Reece Straw.

“The Bluecoat as a site, as a context, is super interesting owing to the building’s history. It’s the oldest art centre in the UK, it’s free entry, and people are familiar with the biennale being on here. The Liverpudlian populace is a public that is as well informed as any other public, so people seem to feel like this work is for them pretty quickly,” Asbestos describes. “My work is public and present. I make a particular effort to get this work out into the world and for it to be seen by people outside of the art profession,” he states.

“Regarding Brexit, we talked a lot about the economy, but we didn’t really talk about culture and what we’d lose culturally from being separated from Europe,” Asbestos considers. “I was keen to use Hansel and Gretel, because it’s a story of Germanic origin that’s pan-European. It’s weird and surreal in the way that European stories are. But it’s a story that we regularly tell our children and it’s a story that’s passed on. I was looking for those inroads into pan-European culture.” With this in mind, Asbestos’ proposal of a new Pop Art that refutes nationalism and celebrates the global is a much needed palette cleanser. His amalgamation of multiple sources to create a visual language which is entertaining and forward-thinking is a much needed respite from an often bleak and oversaturated world of advertising, inequality, and the mundane. As art in the form of television and film was the unsung hero of lockdown, in turn agitating and consoling the bored viewer, so too the artist in a post-Covid society casts spells with their work which trickle into the public psyche.

Cruise Collection 2021, Bruce Asbestos at the Holden Gallery in 2021.

All images are property of the artist unless credited otherwise. Bruce Asbestos’ Ok! Cherub! runs until June 2022 at the Bluecoat in Liverpool. His live catwalk show will take place at the Holden Gallery in Manchester on May 19th. You can see Asbestos’ website here.