I sat down with James Wise, the photographer behind Sweat of the Gods on Instagram. Wise is a Mancunian photographer whose work has evolved from documenting Manchester’s remaining independent shop fronts to a more portrait-orientated practice. We met at The Pevril on the Peak, on a dark Wednesday night, drank Guiness, and I found out how much photography and fishing have in common.

How would you explain @sweatofthegods to a person in the street?

About a year ago, that would’ve been easy. It used to be a very fixed project – focussing on the facades of shop fronts around Manchester. Then it became facades in a certain time period, and then my work moved toward documenting the night time. The night time has a dark and seedy element, and as my work is also becoming more about people, darkness informs this too. I’m drawn to people that have some sort of a dark past.

Why are you drawn to the night time in your work?

I have a lot of dreams set at night. In my dreams there is a continual absence – an absence of people and lots of large empty spaces. Perhaps this is why I have this fixation with it in my work. I also think that the dark creates a lot of mood. The images are more atmospheric and emotive. The night itself is a liminal space, between the inhabited days.

What do you want to say with your work?

I don’t really have a message with it. I work to give my images a bit of unfamiliarity which encourages the viewer to take a second look at things. It’s hard to explain because I don’t really think about it – it’s instinctual. I want to leave it to the viewer to make their own mind up. The message creates itself as my body of work builds up. Having taken photographs for years, it’s all about following my instinct while bettering my craft.

How do you find your subject matter?

A lot of it is on the fly. You go somewhere and there will be something interesting to see. I’ve traveled around England and the work has evolved from documenting interesting shop facades to being more selective. I got into photographing laundrettes for a while because they are unique and dated. You don’t get new laundrettes. I also think my approach is psychogeographical. I grew up in Wythenshawe in the late 80s, and my work leans toward my memories of that. Shopping arcades, laundrettes, places like that, because they have a certain memory. These places also have a sadness and a worn out quality which feeds into my work.

Why do you take pictures of the interiors of shops?

You don’t have much personalised public space now – where people hang their pictures and stuff. It’s an old world thing, so I am looking for personality and personableness when I shoot interiors of shops. Everything is very inoffensive now, not for anyone but for everyone. There is a laundrette in Chorley called The Wash Tub and the owner has put a safari scene up on the wall. Where else would you find that? Taking a photograph of that catches personality. It’s nice to see it, and it’s worth photographing because it’s so rare.

When looking at your highstreet images, I can see something of Tal R’s Sexshops work in it. Who are your influences?

I like Richard Avedon and David Bailey, of course, because their stuff is just fucking incredible. It’s informed popular culture and it’s defined it. I’m not trying to chase what they do, I appreciate what they can do and I can’t. I’m wary of emulating anyone – you don’t want to be a copy. Originally the idea for what I do started with taking pictures inside a barber’s shop called Fred & Alan’s. To me, it was all about the personalised interior, it’s a bit like the pub we are doing this interview in. There is probably a lot of stuff in films that influence me. I was watching The Exorcist the other night, and it’s brilliant, but it’s a two way thing; when you reach a certain point, you can’t unsee composition and cinematography. It’s a blessing and a curse. I love photography because it’s given me so much, but I think I also hate it because I can never escape it. You’re always thinking about it. Find what you love and let it kill you. *laughs*

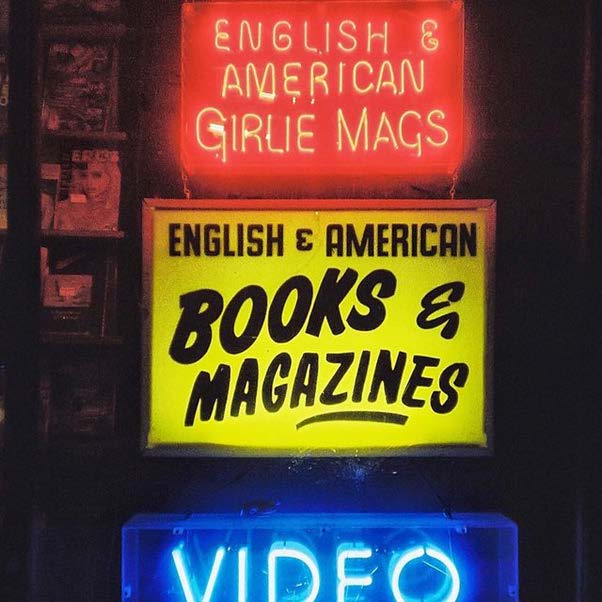

A lot of your work includes neon. Why are you interested in this?

You don’t see a lot of neon, and it undoubtedly has a pleasing visual quality – in person and in a photograph. Originally neon had quiet glamorous connotations, but not anymore, even though that was only 20 years ago. Plus, you can create nice effects with neon that are very

photogenic. For visual creation, it makes sense to use it. It has an energy to it that is significant of something that we don’t really have anymore. In comparison to the shop fronts and neon signs I capture, most modern public spaces – like the Arndale Shopping Centre – are very sterile and sanitised. Neon signs are a bit more real, more lived-in. That sadness is there too.

How do you take portraits?

Working in pubs and with the public all the time was the best thing. It’s made me feel able to approach anyone because I have the “pub chat,” and people love it. Taking a picture is 1% of the process. It’s everything else leading up to it. To take portraits I go out to meet people, it’s like fishing; you wait in a place for ages, see a person, approach them, chat to them, and hope they are receptive to it. I have a big medium format camera – it’s a weird fucking object – so you have to break things down and make people feel comfortable. I used to hate that I worked shit jobs, but they gave me all the skills I need to talk to people. No matter what you do and have done, it

all adds up to cultural capital you can bring to the work. It means that both parties can go away with something they are happy with. You might be out waiting all day, but if you get one picture you’re happy with, it’s worth it. I’ve also asked people to sit for me. I started taking pictures of all sorts of people, but now I want to take pictures of people that have a story. More and more now I can be selective. I’m currently doing work with someone on an album cover, which is an ongoing project.

What type of people do you seek out to photograph?

At risk of being insulting, the uglier the better! I need to have compassion for the person in some way, too, and find them interesting. That’s the motivation for my portraits and why I work with the people I do. There is someone I want to work with at the minute who was involved in quite a famous prison riot in the North West. People of interest, marginalised people, people in the extremes, are the best people because they’ve lived their life. I don’t shoot in a studio – I use natural light and spaces – and I like the gamble of things. Gambling is made positive by

channeling it into photography. The gamble of the photograph – the chance – elevates the photograph.

I can see a calmness to a lot of your portraits. How do you achieve that?

It’s chance. It’s talking to people. It’s a process of disarming people. I don’t think I do it all the time, and I don’t think it’s a conscious thing. My photograph, The Samurai, is of a friend of mine. I don’t think I made him totally comfortable, because while the final photograph is good I wanted it to have more rawness, more ferocity. Still, that image, and that individual, is beautiful. It’s him, and he has a bit of both – beauty and ferocity. Everyone has a softness. We are all caring and compassionate people but the world hardens us. That’s what David Bailey was good at – breaking people down, and finding the essence of them.

What is the furthest you’ve gone to get the shot?

I’ve had to speak to some quite scary people. I’ve spoken to a lot of homeless people, too, but it’s not so much the people but the situation. You feel out of your depth, you have no knowledge of the subject, and it can feel like you’re in too deep. Luckily, I have the chat to ask people questions, and people love that. It’s a very disarming way of doing it. I’m grateful for that, and for having that time in the pub trade. I went through a period of photographing people on the street, homeless or not, girls who might have been working girls, having very frank conversations directed by them. It’s a challenge. If you speak to a homeless person in a wheelchair, are you ready for that conversation? You don’t know what you are going to get. People can handle themselves, but can you handle that, and take a photograph at the end of it? But no, I haven’t had to do anything mad.

The Samurai, James Wise, 2021.

How does your background influence your work?

I was really interested in videography and photography when I was a teenager. As I got a bit older and left home, I started working, drinking and enjoying myself, and not really making anything. Now, I’ve come back to it. I used to think I couldn’t be a photographer because I hadn’t been to university. I’m so glad I stopped thinking that. I realised I came to photography with double the passion for it. Similarly, I used to get upset when I couldn’t stick to anything, but that’s because I didn’t enjoy it enough. Now I have photography in my life and it is a massively positive thing which I am so interested in. I think about it all the time and it is a massive driving force in my life. I think it’s also about having a bit of a “spiv mentality,” doing things on the side, and being enterprising. I’ve always thought about how I can make things work. Working in nightlife has informed my work, too. I’ve lived all over the place – the North West, London, Germany. I went to Berlin for a bit and it was a huge period of growing up. I was escaping a bad time in my life, and I went away for a bit to chill out. It built me up. I got more confident and I now bring that to my work. It was hard and difficult, but you have to have hard periods in your life.

What changes are you seeing around you due to Covid and Brexit?

Not enough time has passed for a meaningful judgement on Covid. It’ll take 5 to 10 years to get something truly introspective. However, Covid has massively changed people. I’ve had a terrible past year, a lot has changed in my life, family, and work, so I think Covid has been significant. I’m focussing on being a bit more patient – doing one thing at a time. My year was chaotic. I was trying to focus on lots of different things; exploring the medium, seeing what I could do with it, how things worked. It was incredibly frustrating, but when I got work out of it, it was good. The problem fuelling my work at this time was frustration. I didn’t work for 10 months, I didn’t have a

job, and I didn’t have a camera because it was in the shop when the lockdown was announced. Brexit’s influence, I couldn’t define: but it definitely has one. The prices and costs of things are an example. I’ve thought to myself, ‘why am I doing film photography?’ You have to be more focussed on taking pictures of certain things. It’s all pressure. I’ve definitely whittled things down.

What is next for Sweat of the Gods?

My work capturing Blackpool, which is a personal project, but it would be nice to break into more commercial work. Additionally, relying on Instagram less. Instagram forces you to produce something for it’s algorithm. It’s a load of bollocks. Yes, it’s helped me with exposure, and I’ve done well with it business wise. But against my website which I’ve recently set up and shows my work in great quality and size, there is little comparison.

Why Blackpool?

Blackpool felt like an obvious choice because I love the Blackpool nightlife. I used to go to the illuminations, it’s a family ceremony. I visited Blackpool often growing up. I love the people there and it’s a bit mesmerising, so I have spent time there doing portraits. Again, I’m looking for people who have had a hard life and have lived an interesting life. I’ve also been taking pictures of Blackpool as a place. It is a bit of a dream land. I’m looking to document the contrast I see between the cold light of day and the intoxicating quality of night. I was going to finish the project in Spring, but I’ve decided it’ll end when I am happy with it. I want to exhibit it because I am getting fed up with Instagram and because I want to return to tangible things, too. I just hope I’ll be happy enough with it, and that it’ll be good enough. I hate everything I do, it’s a horrible feeling! *laughs*

A lot of your fans will know you from Instagram. What is your relationship with the platform?

Instagram asks you to run the risk of having a theme. You have to commodify something so it makes immediate sense. The viewer will “like” it, and then that’s it – and it’s in the graveyard – until you post the next thing. I want to do a curated exhibition soon, but then I’ll have to start thinking about the practicalities of making that happen. Instagram I’ll do because I have to. Instagram makes things into a fad; work becomes homogenised and is alongside all these other people exhibiting through instagram. Instagram is good as a tool, but that should be it. Instagram is one big exhibition itself, it’s ridiculous! All the best and the worst, art, selfies, adverts, all sorts at once. It’s a big arena. While it has helped me get to where I am, it also capitalises on comparison culture. It’s a tough one jostling against everything.

Do you have an interest in the “art world”?

I love it, but I am intimidated by it. I don’t feel a part of it. I rely on people like you because you’ve come and said “you’re an artist, let me interview you”. I do what I do, and people can find it. I tend to do my own thing, but I know people tenuously through Instagram. In Manchester, I’ve had some prints put in Village Books (a book shop and gallery in Manchester). That is my way into the scene. I’ve never really been bothered about the art scene, or felt a part of it. It’s easier to produce your own things. I don’t know why people feel the need to be in a crew producing stuff. The groups I know of don’t seem very genuine. I think it can be self-defeating.

Who is your favourite artist?

Jackson Pollock is my favourite painter. I love Abstract Expressionism. I like the scale of everything, the tempo of how the paint is used, the marks. It’s the scale, the emotion and the feeling of it all. It has a dream-like quality. This can be seen in the style and the impression of things too, there is darkness and empty space – like in my dreams. His work has a vast absence to it. Shame he was a shithouse, though. If you could time travel, where and when would you go? I’d go back to when the dinosaurs were around. It would be fucking madness! Sod the past 100 years, imagine the chaos of that period! Huge creatures smashing around all the plants.

How would you like to be remembered?

In stone, in Southern Cemetry, with an epigraph reading “Peace at Last”.

All images are property of the artist. Wise’s work can be also be found on jameswisephotography.com and risoprints of Wise’s work can be found at sweatofthegods.bigcartel.com