Art is flourishing in Blackpool’s margins. I visited the town with the intention of getting some sort of answer to the question, “what’s Blackpool’s art scene like?”, and found that creative vision and mutual support are the driving factors in the area. With CONCRETE’s ethos of catching the talented on their way up – not down – investigating Blackpool’s art scene at this time is fitting.

Abingdon Studios

“I like your jumper,” Sam tells me after we are introduced. I am at the Blackpool Centre for Independent Living. The centre has meeting rooms, a cafe, a library service and accessible showers, but on Wednesday and Friday mornings, one of the centre’s meeting rooms becomes an artists’ studio. I was introduced to the artists by Tina Dempsey. Dempsey is a contemporary artist based in Fleetwood who works across multiple mediums, including sculpture, collage and paint. Her practice explores coastal environments through an ever expanding collection of found objects and artistic responses to what she discovers. But when I meet her, Dempsey is working in a facilitative capacity for the artist group the pARTnership.

The pARTnership is a project supported by Blackpool’s Grundy Art Gallery, which is part of Blackpool council, Dempsey, and Manchester’s award winning visual arts charity, Venture Arts. The project works with artists from Blackpool with and without learning disabilities. The Grundy’s website describes the project as an Arts Council England funded, 12-month pilot project that brings artists together to share ideas, skills and experiences in weekly art making sessions. Art as a therapeutic means is not new by any stretch, but that is not what the pARTnership does.

pARTnership artist Kirsty Pemberton in the studio, image by Claire J Griffiths

When I visited the group, there was a palpable atmosphere of excitement in the room. The pARTnership’s current exhibition – Watch This Space – had opened just two weeks earlier. Justin Addy, a member of the group who tends toward abstract work, had been to visit Watch This Space earlier that week and this was his first time in the studio since. The artists seemed galvanised. There was very little mucking about; Dempsey passed around materials and work from last week’s session, I said my “hello”s, and the group got on with it.

The pARTnership: Watch This Space at the Grundy.

Artists from the area visit the pARTnership group, including Janine Walker, Claire Griffiths, Joseph Doutbfire and Gillian Wood. They exchange their methods with the pARTnership artists’, creating a dialogue between the core group, Dempsey and the visiting artists. As any artist knows, this kind of reciprocation is critical to evolving practice. In a place like Manchester with an established art scene, this element of art production can often be assumed. Rightly so – it’s integral – but in places like Blackpool it is not a certainty.

One example of exchange developing practice for both parties is between Dempsey and pARTnership artist Lesley New. On the Friday I met her, New is working on an A3 pencil drawing. Dempsey tells me that she had brought a selection of shells from her own collection which have since been used by New to inform her work. Fittingly, the composition New is finishing when I meet her consists of many vertical lines which form an all over geometric pattern influenced by shapes and patterns found in the natural world.

Image of Lesley New’s sculptural work by Claire J Griffiths

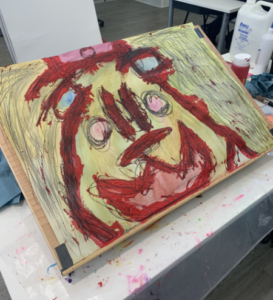

During my visit, Chloe MacFarlane was working on a new version of a previous work she had created which was based on Pablo Picasso’s Surrealist portraits. The woman depicted had large red lips which jutted out past the model’s face. There is a clear lineage between Picasso’s Woman in Beret and Checked Dress (1937) and MacFarlane’s untitled portrait as the artist uses Picasso’s well known Surrealist techniques of distorting faces through exaggerating facial features. Whereas the original portrait depicts a recognisable face, MacFarlane’s larger work is more abstract; in a Chinese Whispers type of approach, MacFarlane looks to her previous portrait instead of the original model to create this new image. The new work is much bigger than the A5 original, and the face becomes more animal-like than that of her previous work – background and skin are the same colour, and the face’s outline is a thick red. Talking to MacFarlane, she says that she likes to take an existing style and respond to it using her own vision. She makes it very clear that she dislikes copying. The work is referential but with its own position. The artist’s dilemma of how good art is engendered is resolved by this method.

Image of an untitled work by Chloe MacFarlane in the studio.

Dempsey tells me, “Chloe’s confidence has improved massively,” suggesting this is a result of making work with the pARTnership and also due to the commercial interest MacFarlane has received. Rod Kippen, of 42nd Street, the Manchester charity for inclusive and accessible mental health and wellbeing support, has commissioned six postcards by MacFarlane. Kippen has also requested to interview MacFarlane. I was surprised to hear that MacFarlane hadn’t always been so chatty, as the artist I’d met had gladly and articulately talked me through her interests in making work, her materials and the piece she was currently working on.

There was one artist in particular who I was keen to meet: Samantha Bragg. Bragg’s painting, David Bowie, (2021) has been used for the Grundy’s Winter 2022 leaflet and a flag with the work on flies by the entrance to the gallery. Bragg paints portraits. When I arrive, she is finishing her picture of Shrek. It uses her signature visual methods – a vibrant background and a head-and-shoulders view of the subject. Shrek, like David Bowie or Robert Longo, is encased in a thick black outline. Bragg started drawing portraits in lockdown – creating pictures of people she found on the internet and from her life, like her family. I was flattered when she invited me to sit for a portrait, and glad I wore my jumper with the swan on it which I think tempted her to let me model. One of Bragg’s works is of Boris Johnson. Bragg’s intentions aside, with the coming to light of multiple lockdown parties, this work offers an inside-as-outside look at British culture – an image made during the legally enforced lockdown of the country’s leader as the country’s leader disregarded his own laws.

Samantha Bragg in the studio working on a portrait of Grundy curator, Paulette Terry Brien. Image by Claire J Griffiths.

That The pARTnership: Watch This Space exhibition has even occurred is radical. There is a perception of art made by learning disabled artists which is rooted in unconscious bias. The Arts Council’s 2018 Making a Shift Report lists: attitudes to disabled people; lack of support; inaccessibile training provision; working culture in arts and museums and a lack of role models as the practical and psychological deterrents holding disabled artists back. To me, it comes down to an understanding of learning disabled people as uncreative, incapable and uninteresting. The pARTnership’s work combats these deterrents. As Dempsey reminds me, “every level” from art production to exhibition is guided by the artists’ choices. This suggests the consciousness of the artists’ practice and further differentiates it from art therapy, which at its core is about teaching individuals to use art materials for expression.

David Bowie, Samantha Bragg, 2021.

Paulette Terry Brien, the Grundy’s curator since 2017, puts it plainly. “The Grundy recognises the quality of these learning disabled artists’ work. We are challenging what people see as ‘fit for an art gallery’. Our role is to champion this work as aesthetic content and to say art can be uninhibited by elevating it through showing it at the Grundy.” The Blackpool ppen show runs in the gallery’s main room and to the right is Watch This Space. It is dynamic, colourful and includes multiple mediums of production. The exhibition showcases the work made by the pARTnership artists alongside work made by artists who visited the group. “If I could take thread and link all these works together the room would be covered,” Dempsey says as I take in the exhibition. I believe her.

Abingdon Studios was established in 2016. It is the first contemporary visual arts studio provision on the Lancashire Coastline. It is a studio space for 10 artists, including Dempsey. The building includes a project space and a window gallery which is a temporary addition supported by the Blackpool Council Arts Service and Heritage Action Zone. Currently, the exhibition space is showing Present Absence. This is an exhibition of Manchester-based artist Parham Ghalamdar’s work in conversation with emerging Blackpudlian painters Reece Adair and Josh Faller. The exhibition gives form to an organised chaos. White cube walls are scribbled with black spray paint effigies of strange creatures which inhabit a sickly landscape. Ghalamdar and Faller’s visually rich, colourful works and Adair’s dark Goya-inspired paintings sit on top of the sprayed scrawl. The effect of using crisp white walls as a canvas for Ghalamdar’s stark, uncanny drawings and then hanging the three artists’ paintings in a deliberately disjointed arrangement is a juxtaposition of the empty and the material. The world of Present Absence is deserted – the canvases offering doorways into regions of mayhem. Considering the three artists’ work – and Present Absence specifically – centres on existentialism and the perceptions of the self, whoever curated the show did a damn good job.

PRESENT ABSENCE, Parham Ghalamdar, Josh Faller and Reece Adair at Abingdon Studios, image by Matt J Wilkinson.

The curator is Garth Gratrix. Gratrix is an artist, a curator and the Founding Director of Abingdon Studios. Born in Blackpool – or “sand grown,” as he calls it – and after a brief stint in Preston, he has been living and working here for ten years. He’s one of the most interesting artists working in Britain that you probably haven’t heard of; Gratrix’s artistic output is conceptual, references the less glamorous and more notional side of art history that is Minimalism, and works from Blackpool not South Bank. In the last five years Gratrix’s career has experienced an array of developments. These include commissioning over 100 artists, creating the Work/Leisure Residency programme for periods of research and reflection for international and national artists, and curating large scale shows exhibiting over 200 emergent artists including the annual Robert Walters UK New Artist of the Year Art Prize. He has had works permanently acquired in the UK and Scandinavia and is currently one of five artists awarded PIVOT supported by The Bluecoat, Liverpool and Castlefield Gallery, Manchester. He is at the beginnings of research around The Coast is Queer and coastal arts ecologies as having the potential to develop a queer peripheral power in the way ‘we’ can see formal frolic and experimentation play out on the edges. “Watercolours? Oils?” Gratrix had joked when considering stereotypes afflicting art. His multilingual practice is so far from both.

Gratrix’s art is distinctly not for everyone – a consideration he is absolutely aware of. His work takes its foundations from marginalised queer experience, as apposed to the work refusing to explore ways to engender congregation and of shared ideas. “Our mission isn’t to convince Blackpudlians that Abingdon Studio art is ‘culture’,” Gratrix states, as we sit in his office at the Studios. “A lot of people in Blackpool need money to feed their kids – they don’t need contemporary art. It’s slightly indulgent of artists to suggest the things we need culturally. I need art for me, and I build what I want to see here, but I don’t go down Blackpool high street with flyers, flogging a dead horse and telling people that Abingdon Studios will change your life. I’m realistic.”

Detail from Shy Girl Flamboyant Flamboyant Flamingo, Crown of Feathers, 2021, image by Matt J Wilkinson.

In a place like Blackpool, to be met with work about lived experience which is abstracted and not immediately penetrable is very refreshing. The expectation of making text-based, design-led work using recognisable forms is not bestowed upon artists in established art centres, so why should it be for artists in Blackpool? There’s an argument that visual art has to have some level of function to subvert, code and symbolise its subject rather than simply be representational. After all, the gallery in the 21st century is often experienced as a leisure pursuit – a day out with a cafe and a gift shop – rather than as a contemplative experience.

Gratrix’s identity and art is shaped by his hometown as he is aware, but as proud of his heritage as he is, he remains critical. “I think it was probably good that I didn’t want to return to Blackpool when I did. Frustration at its flaws led me to think, ‘I’m just gonna say it,’ when I see them,” Gratrix muses. “That turned into people thinking I was actually making a valid point, and asking me what else do you think we should do. Well, I think we need a growth of opportunities; how many empty shops are there in this town? From there we started to do things like an empty shops project.” Speaking about it now, Gratrix sees the limits of such an endeavour. “Putting art by local artists in shop windows is small fry. Looking back at those types of jobs – art in a window does not change the world. However, it pays the artist and gets them an entry level document for their work which they can try and present later for future opportunities.”

From this, an image of Gratrix emerges which matches the praise his collaborators have granted him. Not only is he hard working and ambitious for himself, but also for other artists who have experienced the same obstructions he has. In the arts – like in most arenas – these foils are class, location and identity. Owing to his experiences as a northern and working class queer person, Gratrix has an understanding of the difficulties that incumber emerging aritists. Not content to observe idly, Gratrix’s work has “always been about trying to do something rather than nothing.” ‘Something’ took the form of Abingdon Studios. “That’s where my brain was beginning to go,” he observes, ”there are no spaces that help people get their foot in the door. Blackpool soon became a destination to test my own vision.”

Talking to Gratrix put Abingdon Studios (and to an extent the pARTnership’s work) in context. As he puts it, “everything you’ve heard about Blackpool is true, but it can be explored another way.” When Gratrix returned to Blackpool ten years ago, the only conceptual art production occurring he knew of was Tom Ireland’s Supercollider, a curatorial platform based in Blackpool which featured a nomadic use of space around the town. Gratrix recognises the importance of this project, noting the quality of the work and writing accompanying it, but perhaps more significantly it encouraged him to see where things could go. Ten years ago, the framework for artists to develop their careers simply wasn’t there. “I needed that framework to be built here, so that’s why I did it. Years go by and people started talking more about Blackpool in an unexpected way. Now we have a space for an artistic community who can critically engage with each other. We’ve all got work in development in our studios and are in dialogue. That’s just part of developing practice which so many other people take for granted. Until this was here, that conversation wasn’t happening. You’re always trying to understand what you’re doing now in context, so this conversation is integral.”

Detail from A Man Walks Into a Barre, Twinkle Twinkle Ooh La La, at Air Gallery, 2020, image by Matt J Wilkinson.

Now there are more spaces for art production and exchange, Blackpool is probably quite a good place to make art. First of all – as Gratrix jokes – Blackpool is the DismaLand of the UK. “It’s an attack on all your senses. What do you do when you land here?” he asks. “I say it’s a great place for any artist who genuinely says they are looking to make contemporary art, or art in response to lived experience. If you’ve not been here to understand British culture, then I’d say you’re not really exploring lived experience. Come to Blackpool – it’s the rawest and realest place you can probably visit”. Not only is Blackpool steeped in years of history and holds a unique identity, it’s also not oversaturated with creative production in the way some cities which are renowned for art are. “Of course you want to go where your fellow queer people are and where the clubs and bars are, but then you become part of a mist – absorbed into a group of everybody,” Gratrix suggests. I was reminded of what Dempsey had said earlier when I asked her what the best thing about working in Blackpool was. “We can do whatever we want here. Who’s going to say anything?” Dempsey had smiled.

This is by no means an exhaustive account of art in Blackpool. One exciting new venture in the town is The Old Electric. This theatre and community arts space is run by Melanie Whitehead and is the new home of The Electric Sunshine Project. TESP was formed in 2016 to offer creative experiences which aim to reduce barriers for children, families and adults to connect with their own creativity. The theatre has lots of different types of spaces apart from a stage, including a practice space for musicians and a board room. “Finance is not the only asset we exchange,” Whitehead tells me, “it shouldn’t be a barrier”. Skills can be traded for use of spaces in the Old Electric – a community-minded decision which fits the redevelopment of the building in 2020. Improving the space with Whitehead were a diverse range of adults including some in recovery which inspired her to develop a new drama project – Dramatic Recovery that occurred during lockdown. “A few key people just felt inspired,” Whitehead concludes. Looking to the future, Whitehead is keen to move away from family shows and toward theatre for adults. “I want to show more socially connected theatre. Inclusivity and diversity should be worked into programming because we need to see more people represented on stage. It doesn’t exist, so we have to make it happen.”

By the time I say my goodbyes, it’s getting dark and rain whips around me. That isn’t Blackpool’s fault – it’s England’s. Drinking coffee up the street from the pier, in an empty cafe without dairy milk substitutes, feels like a clear marker that gentrification of Blackpool isn’t on the cards yet. I mull over the Blackpool I’ve experienced and the Blackpool I’ve heard about; the Pleasure Beach, the amusement arcade, sticks of rock, and distinctly British, ageing glitz. This is an idea which is very fixed, but Blackpool isn’t one or the other – it’s both. As commercialisation and pricing out run rife in places like Manchester, I smirk, remembering Gratrix’s earlier comment; “artists working in Blackpool are as far away from all that as you can possibly be, so at some point we’ll all end up here”. I don’t think that would be so bad. Like Bragg’s portrait of me took its genesis in the prosaic, out of the everyday and the ordinary comes the remarkable.

All images are property of the artists unless stated otherwise. Information about Garth Gatrix’s latest show can be found here. You can find out more about Abingdon Studios (including artists Tina Dempsey and Gratrix) here, more about Work/Leisure here, and more about Samantha Bragg here. The pARTnership: Watch This Space runs until 26th February and you can find out more here. Present Absence has been replaced with HERE/THERE which features work by Charlotte Dawson and runs until 5th March, click here to find out more.